On a bright spring Monday recently, with a breeze mussing my hair and the sun warming me gently, I stepped into hell.

A quick history of Auschwitz

For those whose history has become rusty, Auschwitz – located in southern Poland – was the most notorious of the death camps built by Nazi Germany in the countries it occupied or annexed until the end of World War II in 1945. Initially the camp was designed to house Polish political prisoners but was soon expanded to murder Jews, Roma, Poles, homosexuals, Soviet prisoners of war and anyone who in Nazi eyes should not be allowed to live. Auschwitz was not large enough for this undertaking so a gigantic annex, Birkenau, was built.

While inmates also died of a few other causes – overwork, starvation, disease – by war’s end trainloads of people were arriving at the camp daily, with many of the new arrivals marched directly to what they were told were disinfection showers. Instead they found themselves in gas chambers pumped full of a deadly pesticide-based gas, Zyklon B. Their bodies were then stripped of clothes and gold teeth and cremated in giant ovens. The camp functioned as a factory and is the most chilling example of mass genocide of its kind: some 1.3 million people were taken to Auschwitz, of whom an estimated 1.1 million died there.

Today the camp, which stands as a symbol of the Holocaust, has become a museum and can easily be visited on a day trip from the city of Krakow. It is also protected by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

As I walked through the gates of Auschwitz death camp, my blood chilled against the noontime heat. With gravel crunching beneath my feet, a thought kept manifesting itself: more than a million prisoners would have heard this crunching on their way to the gas chamber.

If it was so horrible, why on earth did I visit?

Because I had to.

DARK TOURISM IS NOTHING NEW… A BIT OF HISTORY

Remember the Roman gladiators? The arenas were full to bursting with spectators on hand for the macabre spectacle. In medieval London, the biggest attraction was a local hanging or execution.

In the mid-19th century, Thomas Cook organized tours of British travelers to American Civil War battlefields, and during the Crimean War a few years later, tourists led by Mark Twain visited the wrecked city of Sebastopol – he was even forced to scold his travel mates for walking off with souvenir shrapnel.

And in the Victorian era, tourists toured morgues in London and Paris.

Since time immemorial, death and tragedy have fascinated people and today, these sites share space on Facebook and Instagram with pets, families and scenes of peaceful beach resorts.

But where do you draw the line? Is visiting haunted castles and houses all right? How about Pearl Harbor? Or Inca ruins once used for human sacrifice?

The answer, as you will see, is highly personal.

WHAT EXACTLY IS DARK TOURISM? SEEKING THRILLS OR COMMERCIALIZING HORROR?

But first, let’s get a bit of terminology out of the way, in case you’re wondering what dark tourism IS, exactly.

Visiting sites and places related in some way to violent death or suffering – including mass killings and extermination – is usually called dark tourism. Most times, these places reflect man-made crimes or events (as opposed to natural disaster tourism, which mostly draws people to such events as earthquakes, floods and the like.)

It may also go by the name grief tourism, or even more graphically, thanatourism, from the word thanatos, the Ancient Greek personification of death. Trauma tourism is another word for visiting places that have seen violence.

Any definition of dark tourism carries the weight of uncertainty – the term only appeared in 1996 and its exact meaning is open to interpretation, often used interchangeably with the other definitionis.

This type of tourism is actually on the rise.

Understanding why this is may help explain their draw, although many scholars have explored our motivations and the best they can do is say these are “complex”.

Here are some of things that push visitors towards these sites:

- Some tourists are just seeking thrills, nothing more, nothing less – they want to feel the chill, a bit like watching a horror movie

- Many people are no longer satisfied with spending their vacation on a beach and want new experiences

- They may have seen these sites in the media and are curious

- A site’s fame is a factor, and an opportunity to provide visitors with in-depth information

- Some might be motivated by a perverse sense of relief that atrocities happened to others rather than to them

- Others want to really understand what happened and are genuinely moved by better understanding past violence

- They may feel the need to DO something or feel something

- Cultural relevance is sometimes at play, for example when visitors of African descent tour the slave castles of Ghana or when the children or grandchildren of soldiers visit war sites

- Battlefield tourism, for example, attracts special interest groups who might be keen on history of war or military strategy

- Some people may in some way be participants, survivors or relatives of survivors, visiting to pay their respects or put the past to rest

- The degree of darkness also affects motivation, with some people drawn to darker sites than others

- People may be seeking some kind of collective closure or reassurance

- There is a genuine living desire to sustain and preserve history for future generations

- Many visitors feel empathy and in their own way reach out to those who suffered

- A significant number hope to come to terms with the mistakes of the past – and learn enough to avoid repeating them

- And yes, sadly, there are people who feed off hate and the suffering of others

WHERE DOES THAT LEAVE US: SHOULD WE AVOID DARK TOURISM?

It depends on the site, its history, and your relationship to it. It’s a personal decision – so the more you know about the issue the better.

It also depends to a great extent on which end of the dark tourism spectrum you’re talking about.

At one end are sites related to war and battle, like war memorials and cemeteries. I live in the foothills of the French Alps, where there are a number of memorials to World War II Resistance fighters. I’ve been to many of them, as a homage to those who fought, out of interest, or simply not to forget what once happened. This type of tourism isn’t usually considered controversial.

At the other end is the truly grim type of tourism, such as visiting a place where death is just taking place, like an execution or war zone, or where it has taken place so recently that any visit can only be considered gawking.

Visiting questionable sites can be a positive experience. It can help you gain a better understanding of history and of the world around you – and ensure you contribute to making sure a similar tragedy doesn’t happen again. Your visit and that of others may help contribute financially to an economically depressed area. And if you’ve been affected by the tragedy, however distantly, a visit can help you grieve and heal.

Conversely, there are reasons why you should not indulge in dark tourism. Your presence may be forcing people to relive a tragedy they’d rather forget. You can be perceived – and with reason – as disrespectful and insensitive if you’ve only come to gawk. You could be a voyeur, an exploiter. And, what you’re doing may be plain morally wrong.

An important factor is the behavior of visitors. What seems unacceptable is the trite way in which tourists visit some of these areas, munching on snacks, posing for selfies or giggling where thousands may have died.

This happened during my Auschwitz visit: as we walked along the railway tracks which carried so many people to their deaths, I could hear two women laughing as they stepped over the rails to find the best angle for their photograph. While there’s nothing wrong with taking pictures, this does not qualify as reverent or quiet or respectful.

TRAVELER BEWARE! Just because a site exists and we can afford to visit it does not mean we should. Indigenous groups who ask that we not visit one of their sacred sites should be respected and heeded – and we should stay away. Sites that charge an entry fee that only lines faraway pockets without benefiting the local site or people should likewise be avoided. We must all do a bit of research and think before we visit!

A few things to watch out for

Whatever our intentions, we could easily slip into voyeurism without noticing.

Take displays, like those of children’s shoes or gas canisters at Auschwitz: do they do justice to the pain and suffering that created them?

What about the rest of your trip, the things you do before and after visiting dark tourism attractions, such as eating a fantastic meal or heading for the pub. Would this turn the experience into ‘just one more holiday attraction’, something to be checked off the list?

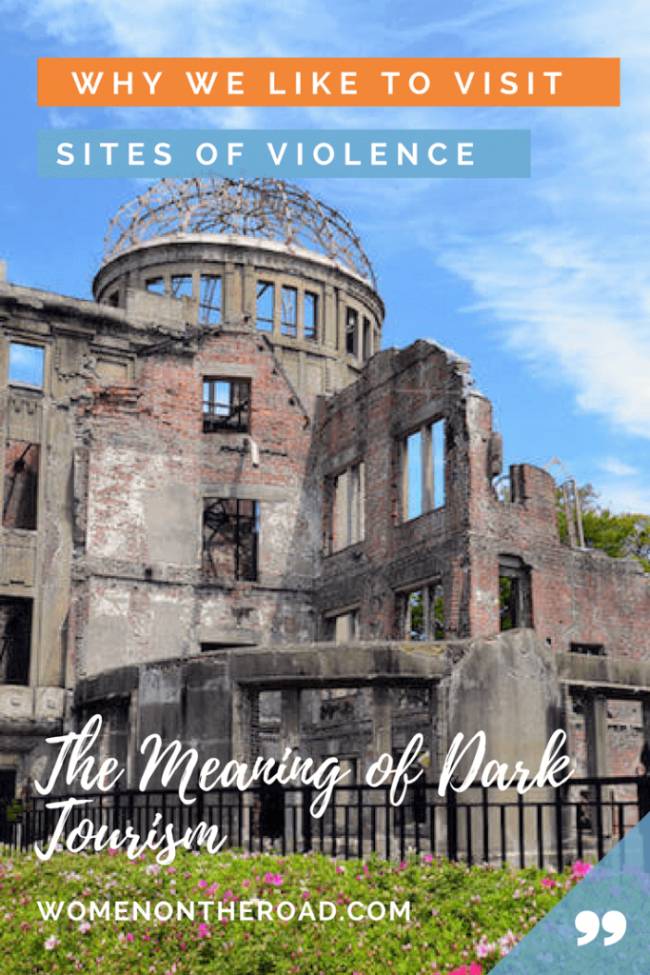

Since Auschwitz, we know what man is capable of. And since Hiroshima, we know what is at stake.

—Viktor E. Frankl

What about the subtle enjoyment of grief, such as feeling grateful one isn’t a victim here, or the sense of oversaturation, when a violent place or event has been so extensively covered by the media that a visit is almost anti-climactic?

Sites may end up commercializing death, such as tours to disaster sites before they have even been rehabilitated. Who makes money as a result? Do your entrance fees go into some corporate pocket or are they used to improve the site and people’s understanding of its tragedies?

These are all questions we should ask ourselves before visiting places of violence. We may not find any answers, but we need to be aware that stepping into Auschwitz or Cambodia’s killing fields is not a lighthearted act.

A QUICK LOOK AT THE WORLD’S MOST POPULAR DARK TOURISM DESTINATIONS

If you’re still wondering what qualifies as a dark tourism place, take a look at this list. They all do, in one way or another, with some more worthy of visits than others. This is a sample but sadly, there are many more.

- Ground Zero, site of the former World Trade Center twin buildings

- Nazi-organized death camps, where six million people died (Auschwitz is but one of many)

- Crash sites, such as Lockerbie in Scotland, where a TWA jumbo jet was blown up by terrorists in 1988, killing 259 people on board and 11 people on the ground

- The Paris tunnel in which Princess Diana was killed in 1997 while being pursued by paparazzi

- Central Park’s Strawberry Fields memorial to John Lennon, who was assassinated nearby outside the Dakota building in 1980

- Most cemeteries, including Arlington war cemetary in the US and the Père Lachaise in Paris

- Soham, a small English town in Cambridgeshire, where two 10-year-olds were kidnapped and murdered by their school caretaker

- Hiroshima in Japan, where the US dropped the first atomic bomb

- Hoi An in Vietnam, near My Lai, where hundreds of women and children were massacred by US soldiers

- Chernobyl, site of the 1986 nuclear power plant accident in the then-Soviet Ukraine, where tour guides use geiger counters to test radiation while escorting visitors around the abandoned city of Pripyat

- Hitler’s mountain residence at Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps

- Fukushima, site of Japan’s tsunami-related nuclear disaster

- Robben Island, a former political prison in South Africa, where Nelson Mandela was incarcerated for nearly two decades

- Cambodia’s killing fields (Choeng Ek Extermination Camp), mass graves for some 20,000 Cambodians murdered during the Khmer Rouge genocide of the late 1970s (see box below)

Cambodia’s Choeng Ek Extermination Camp by Nancy Hawker

The legacy of genocide that the Pol Pot regime left behind – their prisons, extermination camps and killing fields – have now been transformed into mass tourist attractions. One of the many sites is the Choeung Ek Extermination Camp, which was first unearthed by the Vietnamese after their liberation of the Cambodians in 1979. It lies just 15 km southwest of Phnom Penh, and preserves the remains of some 9,000 victims found there. (Some 1.7 million people – 21% of Cambodia’s population – are estimated to have been killed by Khmer Rouge soldiers during Pol Pot’s regime between 1975-1979.)

Upon arriving at the longan orchard with its green fields and silver-tipped trees blowing gently in the wind, I found it hard to believe that so many horrors could have taken place amongst so much beauty. A dirt path winds around the site, with information about each gravesite written across crude wooden plaques. These grassy mounds, around 129 of them, have now all been excavated and marked with the numbers and the gender of those unearthed, and the condition in which they were found.

Prisoners from Tuol Sleng Detention Camp were transported to Choeng Ek by truck, and upon arrival were either detained in wooden shacks that were constructed from wood with galvanized steel roofs and darkened to prevent prisoners from seeing each other, or else immediately executed and thrown into mass graves. Chemicals were then thrown overtop to dissolve the bodies.

Another path through the fields takes you to a large stupa, a Buddhist shrine built to commemorate and hold the preserved remains of those who were killed. Beaten and misshapen skulls peer out from behind thick panes of glass, expressions of surprise and horror still etched on their frozen faces. Propped up against the inside walls of the stupa are the leg and arm bones that once belonged to them.

I was very moved by Choeung Ek Extermination Camp, and although I felt conflicted by paying to see something so tragic, it’s a place that should be visited in order to remember and respect the people who suffered and died there.

My own visit to Auschwitz will stay with me, a terrifying reminder that people who begin life as everyday citizens can somehow become mass murderers given the “right” circumstances.

One thing it brought home to me was the dehumanization that results from numbers. I knew more than a million people had been systematically murdered at Auschwitz. But I didn’t really KNOW that I knew until I saw the photographs of children lined up for gassing, of families tumbling out of packed cattle wagons and the terrified looks of men and women as they clutched barbed wire. I had to feel the chilling claustrophobia upon entering what had once been a crematorium.

Yet I was only a visitor. This, for each individual who died here, was reality.

I cannot allow myself to forget that civilization is a thin veneer indeed, one that can be scraped off with ease, manipulated and controlled. It happened in Germany, in the Balkans, in Rwanda – few countries are immune to a dark side of history.

I understand this could happen anywhere, and that’s a thought I need to hold close.

So yes, I hated my visit – but I’m not sorry I went.

DARK TOURISM TRAVEL RESOURCES

- This academic paper investigates the motivations of dark tourists in depth and this one takes an anthropological approach to this type of tourism

- A visit to Auschwitz is an easy day trip from Krakow. You’ll probably need an organized tour (it can be done independently but it’s complicated and time-consuming). You’ll find them throughout Krakow, easily. Who you book with doesn’t really matter – from what I could see, all tours are nearly identical. The only difference seems to be price and the size of the coach. You CAN do it independently but unless you want to save a few dollars, it’s not worth it. You’ll be shaken by what you see and struggling to find minibuses after such an experience is no prelude to reflection.

- Contrary to what a lot of websites say, you’ll find food and water at both the Auschwitz and Birkenau entrances, along with rest rooms.

- Depending on the weather, bring a sun hat and an umbrella and wear good walking shoes. There’s plenty of walking, outside, unshaded.

- The drive from Krakow is short, around 1hr 15min, a bit more with traffic.

— Originally published on 31 July 2011

IF YOU LIKED THIS PIECE, PLEASE SAVE IT ON PINTEREST!