So what exactly is wrong with war or disaster tourism?

In the thick of the war in Syria, I came across an ad posted by Syria’s Tourist Board touting the attractions of Tartus, a seaside town, almost as though the brutal battles were happening “somewhere else”.

DEFINITIONS: Disaster tourism is the act of traveling to a disaster area as a matter of curiosity. War tourism is recreational travel to active or former war zones.

The examples are legion.

On a visit to Lebanon in the 1980s at the height of the war, I met the Minister of Tourism. More than 50 tourists had visited that year, 50 more than should have engaged in this type of travel.

The waves had barely regressed in the Christmas 2004 Asian tsunami when sounds of cameras clicking could be heard along devastated beaches.

And a year after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, the city was gripped by disaster tourism. Rather than visit for Mardi Gras, people were asking for directions to the Lower Ninth Ward.

So what exactly is it that compels visitors to swoop down on a disaster scene as soon as it happens?

What exactly is wrong with war or disaster tourism?

If it’s not obvious at first, going where disaster has struck − or where danger remains present − has its drawbacks.

Poor behavior is all too common

Often, visitors misbehave at sites. If it’s a historical site where many have died, you may see travelers prancing about taking selfies, making faces, or otherwise ignoring the fact that there were many deaths here.

Visitors may demonstrate a lack of respect

This is closely related to the behavior issue. People have been known to deface memorials or otherwise damage them. I try to imagine what I would feel like if one of those memorials was dedicated to my family or ancestors.

There is a risk of actual physical danger

If someone shows up right after an earthquake, they might face smoldering rubble or flammable gas − or the threat of even worse aftershocks. In a flood, live wires may be dragged under the water, ready to electrocute an unsuspecting tourist, or water-borne wildlife like alligators or snakes may hover nearby. And in a war zone, well, there’s war.

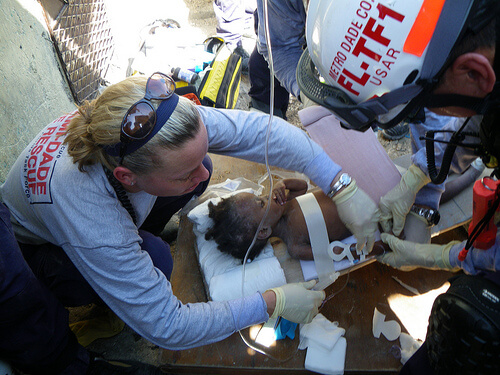

Their presence could hamper lifesaving efforts

A traveler or visitor in a disaster area is close to useless. Most often, they will get in the way of real relief efforts − even if their motivation is pure and all they want to do is offer skills or help. Professional humanitarian workers have mixed feelings about these new arrivals: while they understand what compels them, disaster tourists may do more harm than good.

They may waste precious resources

Just by being there, visitors use up scarce food and water that are needed for victims of disaster or relief workers. Tourist vehicles could obstruct rescue efforts and again, the danger − if a tourist has an accident, precious medical resources may have to be used.

Voyeurism may be resented

A community in the midst of grief over having lost loved ones and their place to live won’t be impressed by tourists traipsing through their former homes. Several neighborhoods in New Orleans took a stand against tours and got them banned after Hurricane Katrina.

What makes people so curious about tragedy?

Whether they are man-made (war) or natural (flood, earthquake), disasters attract people. It’s a complex facet of our humanity and not easily explained.

Just like dark tourism, disasters and conflicts tend to draw the curious.

It could be a taste of authenticity. People are increasingly keen to experience things first-hand, without any intermediaries. Somehow along the way, they lose the fact that many people may have died at the very site they’re so keen to visit.

Rubbernecking is also a natural reaction: people gravitate towards the unusual and the dangerous. Just look at how traffic slows down when there’s an accident on the side of the road − not because there’s no room to pass, but because everyone wants to get a tiny glimpse of what happened if only to feel grateful that it happened not to them but to someone else.

Maybe people are becoming less sensitive, inured to the violence and tragedy seen daily on television and online. A devastated war zone may look less daunting after witnessing beheadings online. It may seem like a game, or worse, fake news.

And maybe it’s superstition − if a disaster has already struck here, chances are it won’t strike again.

Some people simply like to be near danger. And some prefer ‘unspoiled’ places − unspoiled by other tourists, that is. Too bad if the place has been wrecked…

If someone really wants to help, there are specialized agencies that provide avenues to do so. Mostly, they ask for donations but in certain cases, they’ll take people too. An example is the New Orleans Chapter of Habitat for Humanity, for volunteers to help rebuild damaged homes after Katrina, or global groups like Hands On Disaster Response and Relief International.

Is there an upside to disaster or war tourism?

Just because it can get in the way or cause additional harm, does that mean disaster tourism should never take place? It’s a difficult question and a personal one, but there are some benefits to this kind of tourism.

Much-needed money can be pumped into the local economy

Spending tourist dollars at the site of a disaster can be helpful because it forces money back into what have become ravaged economies. This may be true, but will only be helpful once the emergency has actually passed.

A thirst for information

Because we are so much closer to disasters with the advent of instant media, it’s natural to want to see things for ourselves. That knowledge may at times bring home the horror of what has just happened, allowing people to grasp the magnitude of the tragedy far better than by looking at it on a screen.

Never forget

One justification for war or disaster tourism − and again, only after the worst has passed − is to remember what happened in the hope it might never happen again. Keeping the memory of dictators and criminals alive may serve as a warning and as a reminder to those who follow.

That said, the downsides clearly outweigh the benefits of visiting at the wrong time…

When is the right time to visit disaster areas?

At the very least, after the emergency aid and humanitarian workers have gone.

People need a chance to mourn and to come to terms with how their lives have changed.

Wait until the disaster isn’t front-page news anymore. There’s a fine line between disaster, current events, and history. Figuring out how to navigate this line is tricky.

Look at Pompeii − today it is seen as a historical must-see, not disaster tourism. And Syria is a booming tourist destination.

Pay attention to what local people say. Some communities may want visitors to return as soon as possible. Others may want them to stay away. It’s important to respect their wishes.

What to do if you’re faced with a disaster

You might face disasters or dangerous situations of many types, so what follows are selected tips that might be useful for natural disaster survival. As for war, the only viable piece of advice is this: if you’re not a soldier, a humanitarian worker or a journalist, stay away. (Click through for my point of view on travel to dangerous places.)

NOTE: Remember, I am neither a disaster specialist or a an expert in these areas, only a traveler and a writer. I’ve simply gathered information online, as you would, and put it all in one place for your convenience. Always check with the experts!

Areas prone to tsunamis or flash floods

It was Christmas 2004 and a friend of mine had last been sighted along the southwestern coast of India. Then the tsunami struck. We waited tensely until she resurfaced; she was out of range of the tidal waves, but across the Indian Ocean some 220,000 people died.

More than 35,000 of them were in Sri Lanka, where I recently spent some time.

Before leaving for Colombo, I had visited Google Earth and printed out a map of the most likely tsunami escape route.

I also bought a one-month plan from the Tsunami Alarm System, a commercial warning system that sends text messages in the event of a tsunami. I never received a warning, but I was glad to have the extra security, especially since my hotel was right on the beach.

When I arrived at the hotel, the first thing I did was ask about their tsunami evacuation procedure.

They had none. I was glad I had planned my own.

According to the tsunami checklist prepared by the Red Cross, there are a number of steps to take to be tsunami-ready:

- Find the official escape route (and if there isn’t one, plan your own). Make sure it can get you at least 30m/100ft above sea level or 2-3km/2mi inland.

- Check out your route ahead of time in case you have to navigate it at night.

- If a tsunami is triggered, get away immediately. Take an emergency radio with you – a battery-powered oldie, if you have one, in case the Internet goes.

- Finally, wait until the all-clear because one tsunami wave can hide another, larger one.

Tornado preparedness

Like most natural disasters, the best protection is to anticipate, to prepare and plan and avoid – where possible – being taken by surprise.

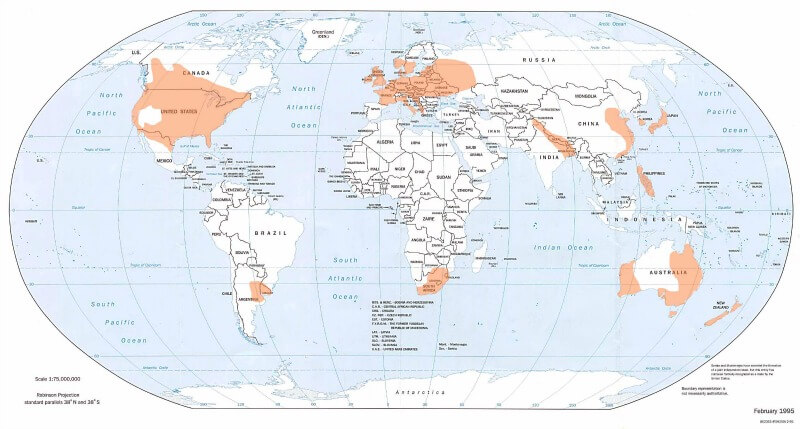

A tornado is basically a violent wind funnel and while many seem to occur in North America, they’re not limited there by any means.

There is a myth that tornadoes don’t cross rivers or bodies of water: that’s what it is, a myth. They can and do cross water, and mountains and all types of rough terrain. Again, a trusty emergency radio will come in handy, especially if internet or phone lines are down.

The best advice I can come up with is the one I follow myself: come up with a plan before all hell breaks loose. You probably won’t need it, but it takes five minutes when there’s no emergency – and those five minutes might be precious if there is one.

One thing to remember: if you’re in a hotel room during a tornado, stay away from windows and head as far into a room’s interior as possible to avoid flying glass and other swirling debris. If your bathroom doesn’t have a window, that might be your best bet. If you have time, pull the mattress off the bed so you can use it as protection.

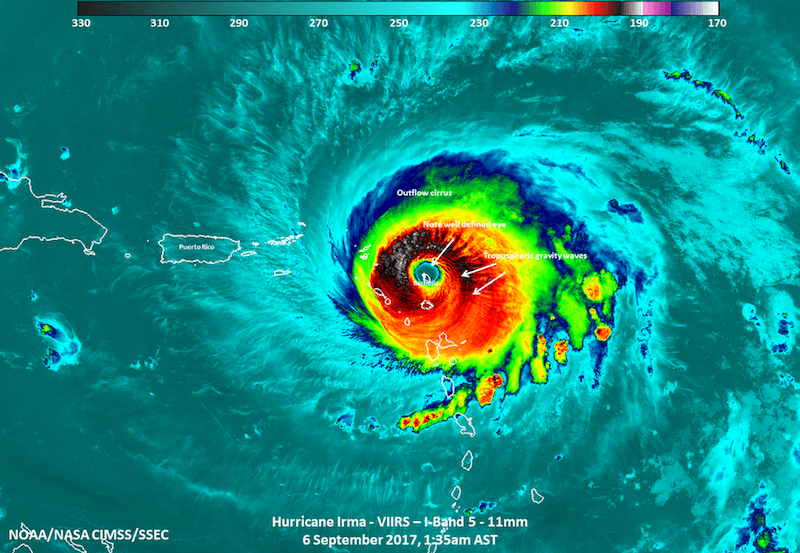

Natural disaster hurricane safety

Hurricanes usually start over water and may head towards land (called landfall). They can be quite deadly but you can usually prepare to a certain extent because you know how much time you’ll have before the storm hits – if the storm hits you at all. It might veer slightly and completely miss your town. Or not. Hurricanes can be tracked but they are still unpredictable.

Being preemptive is just as much part of hurricane preparedness as it is for any potential disaster. Make sure you shop at a nearby store for all necessary supplies including water, easy-to-eat food, batteries, candles, matches and a weather radio, if you plan to ride out the storm. If you have shutters, close them.

Be familiar with any evacuation routes and if you’re told to leave, leave immediately. Hanging in there to ‘ride out the storm’ is, how shall I say, plain stupid. Yes, you might survive the storm. Or you might get stranded or hurt and someone else could lose their life trying to save you. If you have a car, make sure it’s packed with your first aid kit, tires properly inflated, plenty of gas in the tank, and a few snacks and drinks to hold you over in case businesses shut down during your evacuation.

Once you arrive safely, or the storm has passed, pay attention to your weather radio and follow the instructions accordingly. If you can get online, do so. If you’re in a foreign country, ask local people what they are being told to do – and do the same. Make sure you’ve downloaded a translation app to you phone so you can communicate if you don’t speak the language.

And don’t be fooled by a name: a hurricane is known as a cyclone in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans and a typhoon in the NW Pacific.

Find out more about hurricane preparedness from the Red Cross and the US National Weather Service.

Natural disaster: earthquakes and other tremors

Being in an earthquake can be paralyzing. I was caught in a major earthquake in Tehran when I was a child – I slept through the levelling of our building and woke up to a devastated city I still remember decades later. My father had bundled me into a car at the first tremor and in the process undoubtedly saved my life.

If you live in an area prone to earthquakes, then you’re probably familiar with the telltale signs. The earth will shake and the ground will roll until the earthquake stops of its own accord, and there’s nothing you can do about it. If you’re worried, here is a list of the world’s most earthquake-prone regions.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing you can do to avoid an earthquake. There’s a lot of conflicting information around – should you get under a doorframe or not? Under furniture or not? The common wisdom seems to be to curl up next to something solid so a bit of space is left around you should the building collapse. Go out or stay in?

One thing people do seem to agree on is about how to protect yourself should things start to fly around during an earthquake. The accepted advice about earthquakes is ‘drop, cover and hold on’, outlined in greater detail here and here.

Natural disaster: volcano eruptions

While not a daily occurrence, we’ve seen them relatively often in recent times: Mount St Helen’s, Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, Mount Agung in Bali, along with a few rumbles on Mt Etna and outside Mexico City. None of this is comforting if you’re heading for a country with regular or imminent volcanic action.

If you’re looking for information on what’s active and to what extent, you can check Volcano Discovery. Even so, volcanoes erupt without warning so make sure you’re prepared: you’ll need something to protect your eyes, like goggles, and something that will allow you to breathe, like a disposable breathing mask or bandanna. Remember, ash is hot and can burn you so make sure your arms and legs are covered.

Also, volcanic ash can fall 100 miles from an actual eruption so you can still feel the effects even if you’re far away.

For more on what to do in case you’re caught in an eruption, here’s what the CDC has to say.

In conclusion: disaster tourism and dealing with disasters

There’s one piece of advice that is the same for any disaster: be prepared and don’t assume it can only happen to someone else. If you’re in a danger zone, make sure you add some money to your grab bag. It isn’t fair, but having money may make the difference in survival if you can rent some transport to get out of an affected zone. And don’t forget some drinking water purifying tablets or kit.

If you are involved in a natural disaster, you (and everyone around you) will undoubtedly be in a state of shock or acting irrationally so the more you’ve prepared and are operating on instinct, the better your chances of survival.

Be prepared to wait for help. Even in wealthy countries assistance isn’t always instantaneous – so multiply this for a country with weak emergency procedures. Natural disasters may also happen in the middle of nowhere and infrastructure like roads may be destroyed, hampering rescue efforts.

A final word: when an emergency winds down and people’s defenses have been weakened, security breakdowns sometimes happen; shops may be looted or supplies stolen. Even if the all-clear has sounded, stay watchful until you’ve returned to a place of safety.

No one wants to spend their holiday worrying about a potential disaster – I certainly don’t, and that’s why I take a few minutes to plan ahead of time if I’m heading to a sensitive zone. It’s a question of mindset. If you face your concerns and plan for them, you can then let those thoughts go and enjoy your trip. If something happens, however scary, you’ll feel more in control and not as panicked as if you hadn’t given it a thought.

How to avoid disasters when you travel

- Make sure you do your research before you go to a zone prone to disasters, and register with your local consulate or embassy.

- Make sure you have the necessary supplies on hand.

- Develop an emergency escape plan.

- Keep a few essentials on hand: cash, water, a flashlight, your passport, a small radio.

- Carry a card with an emergency contact number. If danger is imminent, use a pen or a marker to write your name and a contact number on your arm.

- If you’re in a foreign country, learn a few words like Emergency, Help, or I don’t understand. Better yet, have a phrasebook with you (an app is fine but in an emergency, you may find yourself without a signal).