Overtourism is a very real concern, and growing. How to cope with destinations that are overcrowded? Do we stay away? Go, and add to the problem? Here are some workarounds, and a bit of hope for the destinations themselves.

How would you react if you decided to travel somewhere and were told: NO, you can’t go there?

Outrage? Disbelief?

Well, it’s happening.

But isn’t freedom to travel our right? Not if it affects other people’s rights…

What if your travels were actually helping destroy the places you love and hurting the people who live there? Wouldn’t you want to do something about it?

That’s the conundrum of overtourism: we are part of the problem, but we can also be part of the solution.

Top tourist destinations in protest mode

For many residents in the most popular tourist destinations, visitors are more of a bane than a boon. They push prices up, trigger the arrival of cheap souvenir shops and harm the environment, all of which have led to public protests.

In Barcelona in July 2024, thousands of protesters took to the streets armed with water pistols, spraying tourists and calling on them to “go home”.

Spain leads the pack – not surprisingly, given that in 2016 it was the world’s favorite country, with a record 75.6 million visitors. Barcelona, Bilbao, Palma de Mallorca, San Sebastian, the Canary Islands, and even hedonistic Ibiza have all been in the headlines for their protests, from demonstrations to graffiti to slashing tour bus tires.

In Amsterdam, locals have taken to the streets in anger about sky-high rents driven upwards by booking agencies.

Bukchon Hanok Village in Seoul, South Korea sees tourists posing for pictures in doorways (relatively innocuous), making excessive noise, discard litter or even urinate in alleys, causing residents to move out and to take to the streets in protest.

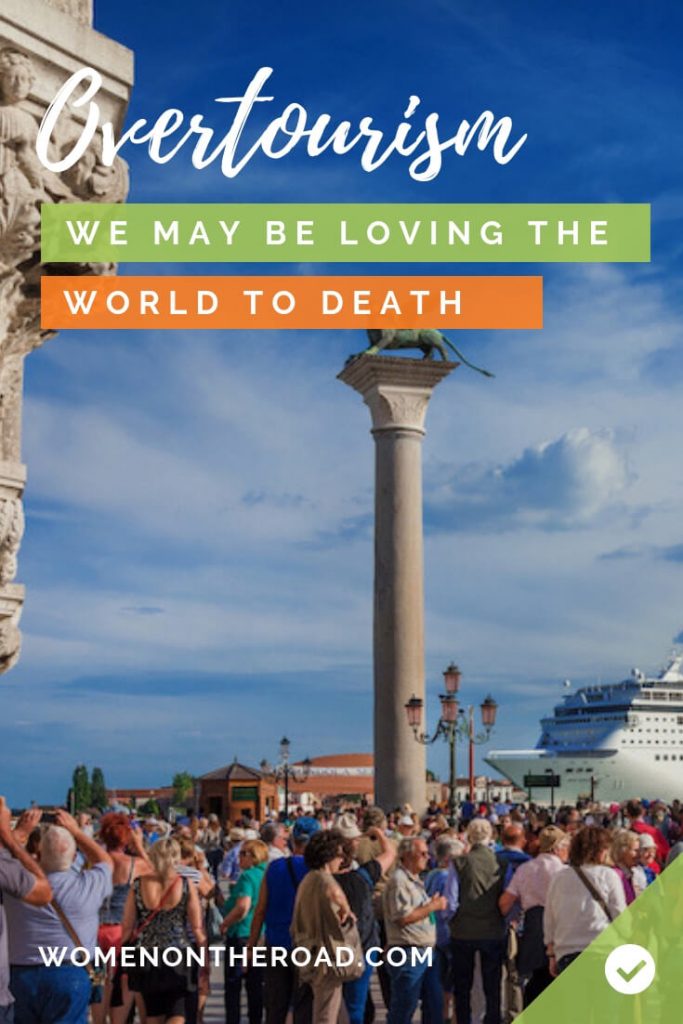

And in Venice, the jostling crowds and the sight of cruise ships looming over centuries-old canals are simply too much to take (I once visited during cruise season and, never again.)

Some alternatives to overtouristed destinations

If we want to help take the pressure off overtouristed places or escape the crowds, why not explore of these alternatives?

- Venice ➤ Ljubljana’s picturesque canals or France’s delightful Colmar

- Bali ➤ Raja Ampat or Sulawesi

- Iceland’s Blue Lagoon ➤ Myvatn Nature Baths

- Dubrovnik ➤ Rovinj or neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Amsterdam ➤ Hamburg or Stockholm

- Barcelona ➤ Valencia’s tapas bars, markets and beaches

- Rome ➤ Verona (it has its own Colosseum)

- Paris ➤ Lyon or Bordeaux

- Cinque Terre ➤ Porto Venere

- Vienna ➤ Mozart’s birthplace, Salzburg

- London ➤ York or Edinburgh

- Santorini ➤ the whitewashed houses and authentic feel of Naxos

- Machu Picchu ➤ its far less crowded near-twin Choquequirao

How did overtourism happen?

According to Skift, who say they invented the phrase, overtourism is “a new construct to look at potential hazards to popular destinations worldwide, as the dynamic forces that power tourism often inflict unavoidable negative consequences if not managed well.” Basically, an imbalance: too many people in a single place at the wrong time.

Simply put, it’s the danger of loving a place to death.

The rise in tourism has been staggering.

In 1950, there were 25 million international tourist arrivals. By 2017 that figure had skyrocketed to 1.2 billion – nearly 50 times higher.

And it’s not slowing down.

According to the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), international tourist arrivals reached approximately 965 million in 2023, about 89% of the pre-pandemic levels.

And predictions for 2024 show those figures are rising.

How on earth did this happen, and so quickly?

- Cheap flights make travel easier, faster and cheaper

- The opening up of China added millions of enthusiastic (and newly rich) travelers

- The cruise industry has grown immensely, with super ships dropping millions of visitors off for the day in the world’s iconic spots.

- Tourism success has always been measured in numbers rather than quality: profits, and “the more the merrier”

- Destinations weren’t paying attention while tourism grew, and grew

- Social media turned destinations into iconic backdrops for Instagram

- he popularity of bucket lists drives more people to visit – “Been there, done that”.

It happened to me…

I get overtourism. Really, I personally get it. In fact I got it before it ever became a word.

I lived in a French medieval village, a prize-winning picture-perfect place.

In winter, it was paradise, with about 40 households and a moody, misty stillness rolling up from nearby Lake Geneva.

In summer, more than a million tourists crammed themselves into four tiny cobblestoned streets.

My window was a favorite spot for itinerant artists, but after the 180th flute rendition of “El Condor Pasa,” I was ready to drop a flower pot on the musician.

Residents rebelling against excessive tourism? I get it.

The benefits of tourism – it is often a good thing

Yet tourism, wisely managed, at a human level, can be a wonderful thing for a community.

- Tourism provides local jobs and career opportunities

- This helps money circulate through communities, especially important in poorer areas, and improves lives

- Tourism generates huge tax revenue (park taxes, hotel taxes, airport taxes, restaurant taxes, boating taxes…) and that in turn benefits infrastructure – better roads and public transport, more money for local education and health

- Income from tourism can help pay for much-needed repairs and restoration of historical monuments and for conservation efforts

- Tourism can earn essential foreign exchange for a country

- Tourism can help promote a sense of community, by highlighting its history and accomplishments and promoting local culture

- Tourism can raise awareness of problems in a destination and can spread the word and bring attention to them when they return home

- Tourism is full of personal rewards: it opens up our worlds by connecting us with others and helping us discard stereotypes we might be carrying around.

According to Taleb Rifai, Secretary-General of UNWTO, “Every time we travel, we become part of a global movement that has the power to drive positive change for our planet and all people.”

Even Spain, where the anti-tourism backlash is strongest, owes 11% of its GDP to tourism. And in Barcelona, heart of many of the protests, half a million jobs rely on tourism, which brings in more than €20 million a day.

The downsides of tourism

Too much tourism can become overtourism:

- Destinations can become overcrowded, while leaving little of value behind: they may buy a few trinkets, and return to their cruise ships at night rather than paying for a local hotel room.

- Places can lose their character and way of life. Crowds can disrespect local customs, for example by wearing unsuitable clothing or behaving unsociably. Too many visitors can dilute local habits, turning a place into a fantasyland or theme park, in the process losing the uniqueness that attracted them in the first place. And let’s face it, local people don’t want their communities turned into zoos.

- We want to live like a local yet too many of us add pressure to services like sewage, garbage collection or water.

- Tourist hotspots attract young people to jobs – but if these young people come from rural areas, their migration to beaches and resorts may help empty villages that are already losing many of their young to the cities.

- Mass tourism can also contribute to social breakdown by introducing lifestyles that are incompatible with local customs.

- Authenticity can be destroyed. We often travel to experience that elusive authenticity, but when there are too many of us, we drive out local residents.

- Mass tourism can cause physical damage. Fragile sites can be threatened or eroded by too many people climbing over buildings and statues or trampling over protected environments.

- Overtourism can undermine a city’s economy by driving up rental prices and displacing locals (who often work in lowly paid tourism jobs and can’t afford to live near their work). This leads to growing property speculation and displacement. While multinationals based across the world get rich, local artisans and businesses are often pushed out. Many of these rentals are illegal, robbing a city of its tax revenue and creating unfair competition for other establishments that do pay taxes and abide by the law.

Are there any solutions to overtourism?

There’s no instant fix, but some of the pressure can be alleviated if everyone does their bit. Every group has a role to play.

What destinations are doing

They’re cracking down, that’s what, and imposing restrictions.

- Some, like Antarctica, Cinque Terre, Dubrovnik, the Galapagos, Bukchon and Machu Picchu, are regulating the number of tourists they allow in or the times they can visit.

- Others, like Santorini or Venice or even Juneau, Alaska, are putting a cap on cruise ships.

- In Rome and Milan, new local littering and loitering laws are being enacted.

- Islands in Thailand and the Philippines have been temporarily closed for rehabilitation.

- Barcelona won’t allow new hotels to be built downtown, and has added plenty of new local laws to discourage tourism (especially given the local street protests)

- Rwanda has limited permits to track gorillas; the Seychelles are banning large developments; restrictions are being placed on climbing Mt Everest in Nepal; Bhutan enforces a (high) daily minimum spend among visitors.

While destinations grapple with their individual problems, governments too are having to step in. With more money and power than tourist authorities, they can shift laws and policies more quickly.

What governments could do

- They could work together at all levels to develop tourism management plans that take a longer view.

- They could decide what kind of tourism they want. If they want tourism at any cost, then don’t blame the tourist for coming. But if they want some sort of preservation, then put in place the necessary limitations – whether cost, or time management or a cap on numbers – and perhaps over time these can be eased.

- They could provide potential visitors with more than just glossy promises of a destination: give us the real story so we can decide not only whether to visit but HOW to visit. I for one would respect a government that told me: “Please come. But we have problems. Here’s how you can make your stay pleasurable while respecting people who already live here.”

- They could tax tourism more (I’m not judging the value of these solutions, just laying them out for you).

- Change the marketing mindset away from the number of tourists to the type of activities they could enjoy.

- They could shift tourism to less congested areas.

- They could restrict not only the number of visitors but such things as the number of flights or automobile access.

And so on. Not all these solutions are viable, some are frankly discriminatory, and they won’t all work everywhere.

But unless authorities confront overtourism and begin finding solutions, some cherished destinations may soon no longer be ours to see. I don’t want Venice to close its gates, nor do I want to be banned from Barcelona.

What we, the travelers, can do

Our actions alone won’t halt overtourism, but they will help, while sending a clear message to residents and authorities that we understand, we care, and that we want to be part of the solution, not the problem.

We need to look at HOW, WHERE and WHEN we travel. Here are a few tips just to start the conversation.

- Avoid high season and travel in low or shoulder seasons in tourist hotspots. No, it’s not possible for everyone – some of us are teachers or otherwise have commitments that restrict our travel windows. But we can try. If we must travel in the high season, perhaps we can adopt some of the behaviors below…

- Indulge in UNDERtourism – visit offbeat destinations or nearby destinations that get far fewer tourists than they’d like (my other blog, Offbeat France, is dedicated to highlighting offbeat destinations in France). Try to uncover places not yet overrun, benefitting a new generation of locals in places that see far less tourism.

- Boycott cruises that visit places under threat, like Venice and Dubrovnik or mega-tours that whisk you from A to B at the speed of light.

- Don’t travel in big groups. Travel solo or independently.

- Contribute to the local economy by staying in bona fide home rentals or stay in a hotel (preferably a locally owned one).

- Engage with the local community when you can. Travel more deeply. During a week in Istanbul, I stayed in the suburb of Sariyer. I rode four or five different public transport systems to get into central Istanbul each morning – but I caught a glimpse of everyday life in a local fishing village on the Bosphorus – and felt incredibly welcome.

- Buy food at the local market and have a picnic. Or choose a restaurant locals frequent (the lack of a multilingual menu is a clue.) Book a meal at someone’s home.

- Avoid places that exploit or pollute: chances are they do far more damage than what we see.

- Give some thought to the attitude of entitlement some of us unconsciously wear like a fluorescent mantle, the one that gives us a so-called right to travel, even where we aren’t wanted.

- Stay near a major attraction and take public transport to visit. Stay in Girona and ride the train to Barcelona, for example. You may discover a new destination that steals your heart.

This will help far more than staying away, which could cost people jobs and local economies their income.

Tourism is not a benign act – it has consequences

As tourists we are often caught between the clashing interests of business (make more money), government (bring more visitors), residents (maintain quality of life) and our own desires (enjoy a holiday in a beautiful destination of our choice).

I can’t read into the future but here are a few of the possible scenarios if things go on as they are:

- Visitors might start staying away. For some destinations, this would be a godsend; for others, a catastrophe.

- Travel might have to become more organized because we have to plan around “allowed” dates and times.

- We could end up paying for entry, like Disneyland, to places like Venice.

- Off-season travel might increase, at least for those who can get away.

- Certain types of travel might be banned – tour groups, for example, or travel at the cheaper end of the spectrum.

- Travel costs could increase as destinations hike prices in an effort to keep people out. Only the wealthy would visit, making travel increasingly elitist.

- We could face antagonism at our destination or outright hostility (as happened in Barcelona).

It’s naive to think that travel revolves exclusively around our personal enjoyment: we pay, fly, run around or lie on the beach for a week or two and return home, all without a thought for what happens at every step of our journey. That lack of consciousness is a part of the problem.

I thoughtlessly stayed in a corporate Airbnb in Barcelona once – because I was lazy. I wanted to be near the “center of the action”. But for my next visit, I thought it through. I stayed in Girona and took the train in, discovering everything the smaller city had to offer me. I ate half my meals in Barcelona, and spent money on attractions there. I contributed to the local economy, but not to raising rents and pushing residents out.

This isn’t about not traveling. After all, I write about places and encourage people to travel, so you could easily say I’m part of the problem. But by highlighting safety issues for women, trying to be objective about a destination and encouraging everyone to travel as locally as possible, I’m trying to behave responsibly.

Thinking ahead is possibly the biggest contribution we can make to reducing overtourism. Thinking about where we stay, when we go, how we engage with locals…

Just imagine for a moment this was happening in your own backyard: busloads of tourists gawking at your house, leaning out to take pictures (bonus points if children or pets are playing outside), some even stepping over your lawn to take a selfie in your doorway, or taking pictures of you doing “quaint, local things” like weeding your garden or having a BBQ.

And hold that thought next time you travel.