He was scruffy, his beard matted and his shoelaces undone.

He was drunk or stoned, or both.

“Foreigners bad! Foreigners go home!”

Evening life had started spilling onto the sidewalks of Blokku, the tony quarter in which Tirana’s elite once lived. Today it is home to chic cafés, delicious restaurants and well-stocked shops.

As he spotted us – two obviously foreign women (for once I wasn’t traveling solo), draped in camera gear and speaking English – he weaved menacingly over.

Almost instantly, a mother and daughter materialized. They scolded him, drawing a crowd. Everyone joined in, chastising the man and creating a barrier between him and us.

He grumbled and eventually teetered off. Half a dozen Albanians encircled us, apologizing, asking if we were all right.

In a country I had been warned for years to avoid because of violence and crime, that was as close as I would come to anything even mildly unpleasant.

My decision to visit Albania was fueled by decades of curiosity.

After all, what do you make of a Muslim country whose greatest hero is a Christian who fought off Muslim invaders? A country so radical it even saw China’s Cultural Revolution as too bland?

Albania is a nation in which history’s fault lines have not been glossed over or refashioned, and whose innate contradictions hang publicly for all to see.

Now courting tourism from the rest of Europe, Albania was until the 1990s the most isolated country on earth, possibly more so than North Korea. But things change fast here. Come 2011 and up it pops as Lonely Planet’s leading destination. In 2015, The Telegraph named it one of the year’s top 20 places to visit. Even in 2019, Harper’s Bazaar UK named it one of the top 10 destinations to visit.

So how could a tiny country, one-fifth the size of England and a bit smaller than Maryland, be both Muslim and not, dangerous and safe, remote and welcoming?

I had to go see for myself.

First, you need to understand Skanderbeg

The national figure is a Christian Ottoman-trouncing hero, an early 15th-century soldier named George Kastrioti Skanderbeg.

His Christian family fought the Muslim Ottomans, lost, and sent their son off to Constantinople (now Istanbul) as a hostage. During his busy life, our hero converted to Islam, became an Ottoman officer, eventually deserted his army, returned home, switched sides, and proceeded to repulse no fewer than 13 Ottoman invasions.

He became the national symbol of resistance to foreign domination, despite the fact that after his death, the Ottomans recaptured Albania and stayed for more than 400 years.

“To one whom later age has brought to light,

Matchable to the greatest of the great:

Great both in name and great in power and might,

And meriting a mere triumphant feat.

The scourge of Turks, and plague of infidels,

Thy acts, O’ Scanderbeg, this volume tells.”

Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser, in his preface to an English translation of Barletius

This fighting against outside enemies is a thread running throughout Albania’s history, as it must be in a country situated at the crossroads of great migration routes.

Everywhere you look here, Skanderbeg stares back at you, a statue or painting or a museum replica of the man who came to be called the “Dragon of Albania“. Or a poem.

If it seems strange that this Christian’s reputation has reached such princely proportions in a country where nearly three-quarters of the population is at least nominally Muslim, it is because religion in Albania is unpacked differently than in many other parts of the Balkans. Albanians see themselves more as secular, a ‘Muslim-lite’ society in which their faith’s ethics and form are respected but aren’t used to bludgeon those who may not believe.

How this ebullient and feisty nation managed to shut its doors and throw away the key for decades is an interesting story and says much about its spirit of independence and self-reliance.

History buff alert: how Albania hunkered down and turned its back on the world

The Ottoman empire long gone, Albania limped out of World War II - it had the ‘good’ fortune of being occupied first by Italy and then by Germany - and swung into the Communist camp, hopscotching ideologically among various socialist friends, from Yugoslavia to Russia to China.

Staunchly Stalinist at first, the country’s dictator Enver Hoxha eventually moved Albania into China’s orbit, at a time when the Soviet Union and China were seriously mad at one another.

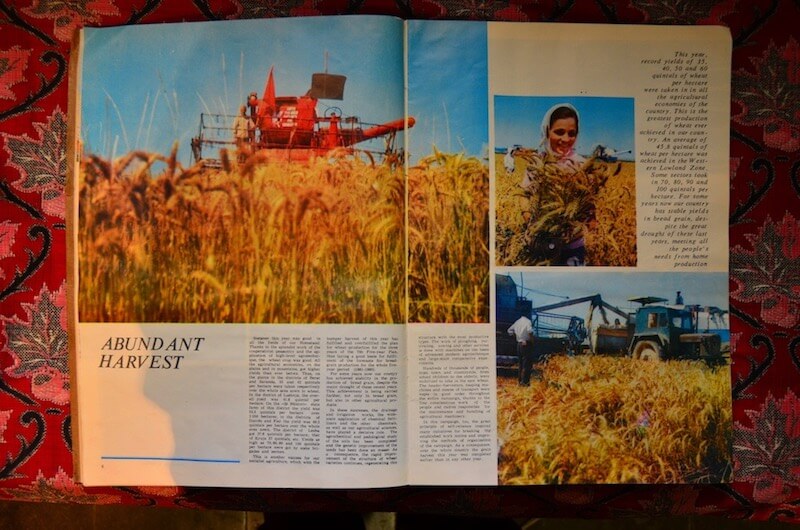

Albania followed China’s suit and launched its own version of the Cultural Revolution, turning against its intelligentsia and creating a peasant economy to fulfil its newly-proclaimed policy of “self-reliance”. The policy, predictably, was an economic disaster and as dictatorship tightened and people went hungry, discontent spread.

No one complained, of course. At least not out loud.

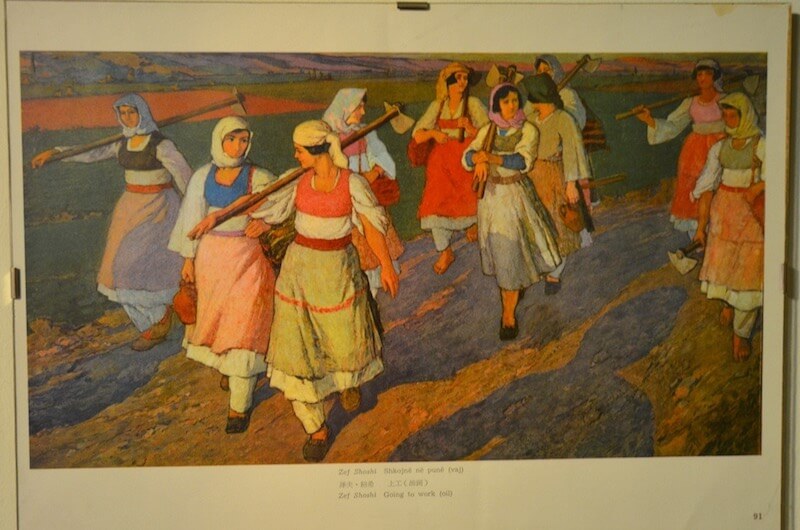

There Was a Time in Communist Albania

Albania drew its proverbial wagons into a circle and cut off the rest of the world, proclaiming itself a paradise. Its brutal leader, Enver Hoxha, simply killed those who didn’t agree with him, including his closest friends and associates.

Hoxha planned for Albania to become the perfect agrarian society. He didn’t fail as much as some would like to think. Literacy rates soared, women in this male-dominated society were empowered, and Albania grew most of its own food.

Unfortunately, the ‘Hero of the People’ also had a few disreputable habits, like using chemical weapons, sending opponents to labor camps, or torturing and killing them.

While Albania has done an acceptable job of protecting its heritage, conservation efforts seemed to have bypassed Hoxha: you won’t find a single monument to the man who ruled the country for more than 40 years. His likenesses were pulled down and hacked away when the Communist regime fell in 1990.

Even though it is more cheerful now, it isn’t difficult to visualize the dreariness of communist architecture in Albania. It’s still there.

The Communist era lives on in the stark apartment blocks or the bizarre Tirana pyramid or the thousands of concrete bunkers that still dot the countryside, which are now protected by the government.

While I have nothing against communist architecture, it can be incomprehensible and ugly. The famous pyramid is a prime example of this.

These days, it sits on a site designated to host the new Parliament building, so there’s a good chance it will be torn down. On the other hand, the government has solicited designs for its refurbishing. Who knows!

I find this so offensively ugly that on some level it should be preserved, if only as a warning to future architects. But it also happens to be a vivid example of Communist-inspired ‘modern’ architecture.

A few collectors kept mementos from the communist era, but searching for antiques yielded only a few old-fashioned radios, some discarded ammunition, and a few rusty military stars. When Albania decided to shed its past, it did so with a vengeance.

Once upon a time in communist Albania, citizens had no contact with the outside world. They had no passports, and when the Berlin Wall fell, most Albanians hadn’t heard the news.

Today, that’s hard to believe. If it weren’t for the bunkers, you’d hardly know that a few decades ago this was a Marxist stronghold that made even Maoist China look liberal.

The end of Communism in Albania

With the end of the Soviet Union and the crumbling of the Berlin Wall, Albania tumbled from crisis to crisis, the best-known of which was a quasi-revolution caused by Ponzi schemes that threatened to bankrupt naive Albanians, still unaccustomed to most things capitalistic.

Panic spread and people rioted, looting military supplies and arming themselves so heavily that an international peacekeeping force was actually brought in to restore order. When things quieted down Albanians kept their weapons, which would come in handy for the crime wave that hit Europe as the Soviet Bloc disintegrated.

It was mayhem. Theft was common, organized crime powerful, and huge parking lots were filled with stolen Mercedes whose German licence plates no one had even bothered to change. Albania had a Reputation, and it wasn’t good.

Fast-forward a few brief decades and Albania is unrecognizable.

Its citizens are (relatively) law-abiding, and society is aligning itself to the rest of Europe. No longer isolationist, it courts visitors actively. When I first began talking online about visiting Albania, numerous groups and individuals reached out to lend a hand, delighted at my interest.

Just because Albania looks outward doesn’t mean everything has changed: in some rural areas the 21st century seems unbearably distant.

Much land can unfurl between dwellings until suddenly, an elderly shepherd appears with his flock of curly-haired sheep, his head covered with a white kerchief, his fist grasping a knotty walking stick.

Further along, a farmer trudges next to his donkey cart, barely moving aside for a passing – and extremely rare – vehicle. Yet an hour away, over the mountain, along those (thankfully few) parts of the coast that have been aggressively developed, you can stroll by a beachside sprawl, a Benidorm of the Adriatic, with concrete highrises, loud music and bad food.

Between these two extremes of emptiness and overdevelopment lies another Albania, one of soaring Alps and deserted coves and near-white stretches of immaculate Ionian beach, of pristine pine forests and rapid rivers and incomparable ruins that have survived since Antiquity.

A look at Albanian history: a date with Antiquity

Illyrians? Really?

One hot summer afternoon I visited the magnificent Greek and Roman ruins near Fier at Apollonia, whose lower harbor once held up to 100 ships, it is said. Apollonia was first settled by the Illyrians, that mysterious lineage which, as we know from Ancient History class, are a bygone Balkan tribe about which… we know virtually nothing.

Only a tiny portion of Apollonia’s vast hilltop city has been excavated and restored, with mouthwatering ruins jutting enticingly out of the parched ground, begging to be unearthed and scraped back to life.

A lone bus waits in the shade for straggling tourists, more concerned about air conditioning than graceful columns or perfectly-shaped amphitheaters. The caretaker looks a bit wistful, gazing as a savant would upon a bevy of uncomprehending first-year students. “You are missing so much!” he must be thinking, running a handkerchief across his sweaty forehead. Their short hour here can’t begin to cover the ground that centuries have started to hand back.

Among the ruins is a gem of a museum housed in a former 14th-century monastery, reopened in 2011 after a 20-year renovation. This is where the products of all these digs come to rest, away from the heat and erosion of the seasons. The interior is cool, like a Moorish patio, and the sights irresistible.

Far more frequented and better restored are the ruins of Butrint, a UNESCO World Heritage site also once inhabited by Illyrians − prime Albania tourist attractions. Butrint is easier to reach than Apollonia, a comfortable day trip across the strait from the Greek island of Corfu. I arrive from the North, along the winding coastal road that overlooks hundreds of mussel nets thrown across turquoise bays.

The Illyrians may have been here first but Butrint welcomed Greeks and Romans, Byzantines and Normans, Venetians and Ottomans and everyone else whose presence is still felt among the crumbling remains.

Sitting on an ancient stone bench within sight of the Roman amphitheater, I imagine wealthy merchants sailing up the canal into port, gazing in admiration at the massive fortifications of the town and its elegant temples, fountains and mosaics, and even its two basilicas, vestiges of Butrint’s confused past (the site was eventually abandoned due to extensive flooding).

Despite its popularity, this compact site doesn’t feel crowded; there is always a tree under which to rest, a seashore upon which to gaze, and walls to separate you from other visitors should you wish to avoid them.

My final foray into Antiquity is situated at the top of a lonely, windy hill above the village of Lin, itself perched over luscious Lake Ohrid. On a clear day, you can easily see Macedonia.

Once you begin walking uphill from Lin, children will follow you and one will surely run off to find the man with the rusty key to the even rustier gate. He will be thrilled to let you in as he gently lifts the corners of plastic covering centuries of delicate mosaics in dire need of conservation. I look around this abandoned site and try to visualize people going about their daily business. I can’t. It feels old and alone, wrapped in sadness, waiting to be dusted off and rediscovered.

My friend Elton Caushi, who runs the Albanian Trip travel agency, calls it “Europe’s most exotic destination.”

He hurries to add, “But it’s changing rapidly.”

Two marvels of Byzantium

After Antiquity came the Byzantine Empire, which has always made my head swim. Its near-divine craftsmanship emerged from a deeply Christian medieval society which at one point covered most of the Mediterranean basin. That empire would last more than 600 years and would scatter architectural marvels in its wake.

The Forgotten Churches of Voskopoje

The Albanian village of Voskopoje harbors hidden treasure: remnants of extraordinary ecclesiastic art, murals, and frescoes that unexpectedly survive in a handful of ancient mountain churches. These were built by rural Christians during the Ottoman Empire.

It is a miracle they’re still standing, having been battered by just about everything: war, erosion, abandon, graffiti.

The churches of Voskopoje – or Voskopoja, as it is also spelled – have received some protection from the government, the European Union, and foreign groups yet the job is far from done, and villagers, many of whom are caretakers for the churches, are unsure about when – and if – the restorations will be completed. Worse, in 2018 the churches were listed among Europe’s most threatened. At least they’re on some radar screens…

The churches aren’t all near one another, but the major ones can easily be covered in a day hike. The mountains ringing the town are peacefully beautiful, and it’s easy to imagine packing a picnic and setting off to see the frescoes.

The road from Korça takes under an hour, and taxis will usually take you up. Stay the night in one of the local hotels if you can. If you plan to hike, a guide would be useful because signposts are rare and maps more so.

It would also help to have an Albanian speaker who can find the priests in charge of each locked church – and each key. Ask at the café – or pretty much anyone in the street.

What you’ll see is truly stunning: colors and designs whose robustness has saved them from almost certain destruction, true artistic and spiritual beauty that should never have been allowed to deteriorate.

The next empire

Throughout the second millennium, Albania was caught up in the great currents of Balkan history, becoming Muslim as the Byzantine Empire wore itself out and the Ottomans poured in. Mosques dot cityscapes as frequently as churches, but to me, the heart of the Ottoman Empire lies in its architecture, in the buildings of two cities in Albania, to be precise, both protected by UNESCO.

The first is Berat, also called the ‘Town of 1000 Windows’. The reason is obvious.

Towering over the delicate Ottoman housing is Berat Castle, more of a fortress, and certainly more Christian than Muslim. The city’s steep hills and cobblestones must have been inspiring since this is where Albania’s greatest artist, the 16th-century Onufri, was from. If you’re curious about daily life in Berat, the kitschy but well-planned Ethnographic Museum is filled with household furnishings and objects that reflect the past. I was struck by the filigree screens behind which the women sat – making sure they were heard and not seen.

The other remnant of Ottoman architecture is Gjirokaster, whose urban landscape is less airy, more decorative. Its sloping stone roofs have earned it the nickname ‘City of Stone’.

The best view of the graceful buildings and uneven streets is from above, from the Citadel (although modern architecture has somewhat spoiled the view and nearly scuttled the city’s bid for protection under UNESCO).

Sorry Albania, not everybody loves you

Albania was built on waves of immigration – from Illyrians to Greeks and Romans to Byzantines and Ottomans and Communists and more, who often won their right of residence by war.

A prize for some, a curiosity for others, few visitors have ever reacted with indifference to Albania. It is a country that elicits strong reactions.

Writing in 1848, the Scottish diplomat and traveler James Henry Skeene divided Albanians into four tribes: the Gheghides of the North, good soldiers with “natural stubbornness”; the “most handsome” Toskides and their beautiful women further South (Lord Byron called them “slender and agile, both strong, vigorous, and perhaps the finest race in Europe”); but things spoiled with the Liapides, “the worst of the Albanian tribes living only by rapine and murder” whose “evil name has sullied the reputation of the whole nation”; and finally, in the southernmost tip across from the Greek island of Corfu, the Tsamides, whose fair hair and blue eyes seemed to somehow set them apart.

Flora Sandes, in An English Woman-Sergeant in the Serbian Army, mused: “I had always pictured the Albanian peasants as a very fine picturesque race of men wearing spotless native costume, and slung about with fascinating looking daggers and curious weapons of all kinds, but the great majority of those I saw, more especially in the small towns, were a very degenerate looking race indeed.”

Nor did Joseph Stalin, the Soviet dictator, think much of them: “[The Albanians] seem to be rather backward and primitive people… ” (and I’m leaving out the worst of what he said).

Even the FBI at one point is believed to have said, “Every country has mafias, the Albanian mafia has countries.”

If this is all you’d read, one could understand if you chose to give it a miss. But you’d be making a grave mistake.

Don’t worry though – the naysayers are the minority

Take Lord Byron, who in Childe Harold described Albania as a country of…

“Morn dawns: and with it stern Albania’s hills…

Robed half in mist, bedewed with snowy rills.”

Even in his Letters and Journals, Byron seemed to clearly grasp Albania’s underlying identity. “I like the Albanians much; they are not all Turks; some tribes are Christians. But their religion makes little difference in their manner or conduct. They are esteemed the best troops in the Turkish service.”

One of the best-known “modern” foreign writers about Albania was Edith Durham, who in the early 1900s in High Albania remarked upon Albanians’ resilience: “[They] are strewn with the wreckage of dead Empires – past Powers – only the Albanian goes on for ever.”

An even clearer vision of the indomitable and resilient Albanian character comes to us from an unnamed Bulgarian observer, writing in 1924: “…isn’t the Albanian, who, being a slave, did not allow enslavement, freedom-loving? This is a question that could hardly be understood by anyone who has not lived in Albania. The most liberty-loving people in the Balkans are the Albanian people. The Albanian, taken alone, as an individual, is an anarchist by nature. He would brook no bondage let alone on his people, he would not let anything, seen as possibly humiliating, befall his house. The Albanian house stands alone and apart from the rest…”

And so it has done, proudly.

Rediscovering Albania’s adventurous soul

While Communist memorabilia has its draw, Albania’s heart surely lies in its glorious nature, its mountains and coastlines and river valleys. Anyone who loves adventure and wild places will be drawn here, although years of stagnation pushed Albania towards overdevelopment, especially during the 1990s but things have started slowing and laws now protect some of the more important sites.

Take the country’s coastline, whose nearly 400 kilometers of Adriatic and Ionian shore are still isolated – hidden coves, abandoned submarine bases, underwater wreckage or crumbling fortresses you can only reach with effort.

If you’re a calm-water kayaker, as I am, you may never have a chance like this again. Until a few years ago, privately-owned boats were banned (they had been used to illegally ferry migrants and drugs) so coastal waters were empty. Small vessels can now be bought, and Albania’s sparkling blue waters may soon turn into shipping lanes if this newfound freedom of the seas isn’t managed in a sustainable way.

The pollution of modern mass tourism has already begun along a few Albania beaches where entrepreneurs rent out jet skis by the minute. Clients are often inexperienced and rowdy and there are few rules. Thankfully these resorts are still rare and authorities are taking notice and acting accordingly.

Right now there’s enough coastline for everyone and the best beaches in Albania are those that remain relatively undiscovered.

For years, unbridled and unauthorized building was the norm, with ugly concrete structures emerging from the ground nearly overnight in defiance of any law. The free-for-all is past and buildings that don’t follow security and cultural codes are slowly being demolished. There’s hope that the cheap highrises built quickly to cater to rock-bottom tourism and mar the silhouette of crushingly beautiful sunsets won’t become the norm.

Take Saranda in the South, long a vacation spot of Communist elites but today an extended string of cheap eateries, traffic and pounding music I was in a hurry to leave. But it did have glorious sunsets. Another is Durres to the North, a day trip from Tirana and a popular Albania vacation destination for landlocked Kosovars. Both cities boast stunning natural beauty and both are developed to breaking point.

Sitting on an empty beach is a worthy pastime but if I had to categorize Albanian tourism – and by now it should be abundantly clear that this is no simple task – I would probably label it an ‘adventure destination’.

I say adventure because despite its small size, the tiny population (quite short of three million) simply doesn’t fill every nook and cranny, leaving the rest of us an abundance of wilderness, abandoned roads, fast-flowing rivers and massive mountains in which to play.

Rapid development may have inadvertently done adventure travelers a favor.

A network of newly-surfaced valley roads has prompted drivers to abandon the old, winding strips of dirt and tarmac that cut straight across the mountains (under Communism, flat lowlands were reserved for farming, not driving, so mountain roads zig and zag along at dizzying heights).

What happens when old Albanian roads go to heaven? They become amazing cycle paths, almost empty of vehicles, and the few cars and buses that do brave the yawing potholes are easy to avoid – you can hear them for miles before you see their dust plume.

Or you could strike off into the forest for some off-road biking – the mountains between Korce and Elbasan, for example, are solitary and pristine.

If your bike has a motor this must be paradise, with twisty roads that soar and dip from ragged peak to mellow valley through extraordinary mountain passes that could put some other European mountains to shame. Even in the remotest corners, like Lake Komani in the North, motorcyclists become near-gymnasts as they heave their bikes onto the rickety ferries. Worth every effort, they tell me.

Riding the Blue Rustbucket on Lake Komani, Albania

Getting to Lake Komani – a man-made reservoir – is a three-hour undertaking, one that begins at 5 am in Tirana.

The smooth highway lulled me into near-sleep until we started climbing, the road becoming narrower, the potholes larger, and the precipice steeper with each hairpin curve.

We rose and fell, skirting mountain slopes and lakes, across countryside so calm and abandoned the few scattered farms seemed to have been placed there by an unseen hand.

Komani ‘town’ was a pit stop of a restaurant, a bar and a concrete slab of a wharf along which a few stubby barges floated lethargically.

My research had indicated that crossing Lake Komani requires a car ferry, but when we arrived, said ferry was nowhere to be seen, having been beached the previous Wednesday because it cost too much to run. (According to the latest news, a regular ferry is back on the lake.)

Instead, we were welcomed aboard what I affectionately nicknamed the Blue Rustbucket.

Other than a wing and a prayer, there was really no reason this ferry should still be afloat.

It was a perfect little ferry: rusty, smoky, layers of welding patchwork gluing it tentatively together with a few humps and bumps around the body.

The journey across the lake lived up to its reputation as “one of the world’s classic boat journeys” for every minute of the four hours or so it took us to cross.

High mountains embraced the smooth reservoir, their sides dropping at nearly straight angles into the calm water, a jumble of ruggedness, wilderness and solitude.

At one point, we just stopped. The motor died and the two machinists tapped around with a hammer to investigate. We drifted so close to the mountain wall that we actually pushed the boat back with our feet and arms. A bit of clearance, a bit of luck. and the engine sputtered back to life.

Onward to Fierza! To the end of the lake!

The country’s fast-flowing rivers, which might as well have ‘kayak me’ stamped all over them, are superb, whether you’re heading for the Fjosa River (category 3 and 5 rapids) near Permeti or the 13-kilometer Osumi Canyon or the Devol River, another category 5. I’d be in favor of supporting local businesses where I could, and the rapid development of adventure tour agencies means guides, logistics and equipment are ready and waiting.

You can cycle, bike, kayak, raft, sail, swim… but in a country whose surface is 60% mountains, how could you not hike?

“It’s pretty much unexplored,” says Armand Jegeni of Outdoor Albania, an adventure travel agency. “You can also camp pretty much anywhere.”

Still, I’d rather wander over to any inhabited house and ask for permission. Many Albanians are armed – remember those weapons they ‘rescued’ from army stocks during the troubles of the 1990s? You don’t want to test their genuine hospitality by roaming uninvited onto their land.

Into the Albanian Alps

That said, highlanders are extremely hospitable, even more so than the average already-welcoming Albanian, so if they encounter foreigners on their doorstep they might just ask you in. If they do – accept immediately because as a guest you’ll be treated with respect and if you’re really lucky an Albanian feast will appear, a range of Mediterranean and Balkan foods that you will be fully expected to eat down to the final morsel.

A word of caution: if you’re heading into the mountains you should take a guide with you. Paths are not always clearly marked, maps can be inaccurate, few people speak English, and in many places your cellphone won’t work so if you have any problem at all, you’re stuck. Not to mention the common summer forest fires…

Until recently, a few straggling hikers showed up each year in Valbona, the main jumping-off point for mountain hikes. Behind the mountains, Montenegro hides. Under Enver Hoxha, troops were stationed here to prevent Albanians from escaping North. Now, on the contrary, escape of the sporting kind is encouraged.

The Alps are chopped up into several national parks with little budget or staff, parks in name only, although there has long been talk of joining up the area’s parks into a larger Albanian Alps Park. This would not only keep the increasingly popular area pristine but improve facilities for visitors, with important things like trail markers and signs. A transboundary Peace Park has also been under discussion…

Despite the mountainous alpine terrain winter sports haven’t really taken hold. There’s no decent equipment.

“People here understand snow and in winter when it gets thick there’s a lot of dithering about whether you can walk on top of it soon,” said Catherine Bohne of the Hotel Rilindja in Valbona (you can reserve by contacting Catherine at this Facebook link). “We either wait, or we rig up ‘snow shoes’.” They do this by strapping their shoes to plastic crates or whatever else is available. Not quite your modern Alpine resort. Yet.

My Albania itinerary

So how does one actually visit Albania? Getting here is relatively simple, either by flying to Tirana directly or to a neighboring country like Montenegro or Kosovo and taking the bus over the border. If you’re planning an Albania roadtrip with a car, your best bet is the ferry from Bari in Italy.

But how you get here doesn’t matter. Just get here. Anytime is the best time to visit Albania.

After much consideration I decided to visit the country in a broadly clockwise direction, traveling both by rented car and by public transport. I began my journey in Tirana and headed North towards the Alps, swinging into Kosovo and back to Tirana before heading South to Lake Ohrid and Korce. Crossing the mountains of Central Albania to Berat, Permet and Gjirokastra will get you to the South and to Saranda and Butrint. From there it’s a clear path back up North, along the coast and through the Llogara Pass towards Tirana. To see the country superficially would take at least two weeks, and that’s without stopping along the way to kayak, climb or cycle. But it will give you a chance to see some of the best places in Albania.

The land of the double-headed eagle (the national flag) is rarely predictable. Bright, shiny roads cover the main routes but some older strips are so narrow car tires seem to balance over a cliff’s edge as you inch along. At first encounter Albanians can seem rather standoffish; the second time around they’ll be inviting you home for a meal. It is a friendly country where people are at least as curious about you as you are about them.

Of course it’s a cliche but Albania is a country of contrasts – not only of cultures and religions but in everyday life, with today fighting hard for a foothold against the past. Wifi may be easily available, but the biggest traffic hazards are erratic donkey carts.

There’s something about Albania

Albania has a wild heart and a welcoming smile, which you’ll feel if you stay more than a couple of days.

Part enchantress and part heart of darkness, it doesn’t quite feel the same as its neighbors – it is neither Slav nor Mediterranean, neither fully Muslim nor Orthodox, not ancient and not modern, not Eastern or Western but a superimposition of cultures, histories and stories, many of them still unknown. I mean, how many famous Albanian people can you name? There’s King Zog (more famous for his unusual name than for his actions), Enver Hoxha, and Mother Teresa (an ethnic Albanian born in Macedonia). The prizewinning author Ismail Kadare is known in some circles. I can’t really think of anyone else, can you?

Albania. Lofty, mighty, rugged, pristine, perplexing, diverse, welcoming, a big empty playground just waiting for the kids to arrive and the games to begin, its transparent clear waters, uncrowded mountains, timebound villages and incredibly hospitable people not yet overrun by tour buses. Albania, land of historical overlays, crossroads and clashes.

As my friend Elton Caushi says, “If you’ve visited the rest of the Mediterranean, then come here.”

I would disagree. I’d say come here first. But hurry. Things are changing as I write.

Essential info about Albania

Where is Albania?

For those not familiar with the region, Albania is in southeastern Europe. The stunning Adriatic Sea meets the west coast, while Kosovo and North Macedonia lie to the east. Montenegro borders Albania to the north, and Greece hugs the southern border.

What language do Albanians speak?

Most people speak Albanian, although dialects vary depending on the region. However, because of the convoluted history and proximity to other countries, you’ll find a bit of Italian, Greek, French, German and English.

Albania visa requirements

Depending on your country of residence, you may not need a visa to enter Albania; some countries have visa exemptions, others get visa-free entry. For example, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the United States can stay up to 90 days. Check online for up-to-date requirements for your country before you plan to spend your holidays in Albania.

Things every Woman on the Road should know about Albania

- If you’re slightly adventurous this is a perfectly fine destination for women travelers.

- Driving in Albania is still a bit erratic as people come to terms with new cars and good roads, but the police are clamping down, hauling people off to jail for drunken or dangerous driving. In Tirana, pedestrians weave around as much as the drivers so keep your eyes open whenever you get near a street.

- A wonderfully helpful travel agency – the one I used – is Albanian Trip. Make sure you deal with Elton Caushi directly. He has all the best Albania travel tips.

- If you’re heading towards the Alps, Journey to Valbona can organize an Albania travel guide who will help you avoid some of the steeper dropoffs and will get you to water when you need it. My friend Catherine and her boyfriend Alfred also run the Hotel Rilindja alpine lodge, which you can book through their site.

- The public transportation network is extensive but slow. There are buses and furgóns (although I’m told the furgóns are being phased out) that crisscross the country but most leave early in the morning and don’t travel much past noon. Reaching all the amazing places to visit in Albania can be time-consuming. To get from one town to the next might take you half a day at the very least. The new road network makes a car trip worth a thought, and Albania in recent years has stocked up on new-model car rentals at relatively reasonable prices.

-All photos by Anne Sterck unless otherwise noted.

— Originally published on 08 August 2017

SHOP THIS POST ON AMAZON

PIN THESE PICTURES AND SAVE FOR LATER!